Elixir’s power comes from ability to handle concurrency very well. This blogpost and the next blogpost cover some basics to get started with concurrency in Elixir.

Process vs. Threads

A brief background on a thread vs. process. Both are independent sequences of execution. The main difference between the two is that threads share memory and system resources where as processes do not. In fact, a process creates threads. A process usually starts off with one thread, but it can create additional threads. Threads can run into problems such as deadlock and issues with manipulating data. This isn’t the case with processes, and they actually be run on separate machines since they do not have to share resources and they can run parallel to each other. Since threads are created within a process they can communicate with other threads within the same process. Communication between processes is more difficult and it is called interprocess communication.

Elixir Processes

Typically processes are heavyweight items, but Erlang has various efficiencies that allow processes to be lightweight and easy to create. Since Elixir compiles to Erlang, it took advantage and built off these features. A process has something called a Process Identifier (PID), which is a value that represents the process. In Elixir, we can create a new process with the keyword spawn/1.

iex> spawn fn -> 1 + 2 end

#PID<0.82.0>

Here we passed a function to a process. This returns the PID, not the result of the function. The spawned process executes the function then dies.

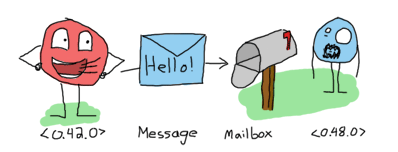

One of the most important parts about processes is sending messages between them. Here we introduce the concept of a mailbox. A process sends a message to another processes mailbox via the send/2 function. Messages are kept in the order they are received. When a message is read it is taken out of the mailbox. Here’s a picture from a helpful Erlang article.

The shell itself is a process and you can see its PID by calling self/0

iex> self()

#PID<0.80.0>

We can send messages to a process (for example our shell) with the send/2 function, and read messages with the receive/1 function.

iex> send self(), {:foo, "bar"}

{:foo, "bar"}

This puts the {:foo, "bar"} in our Shell’s mailbox, but it has not been read yet.

iex> receive do

...> {:foo, message} -> message

...> {_, message} -> "this will not match"

...> end

"bar"

This part will read all the messages from the current mailbox and return the value specified. Here we patterned matched on what was in our mailbox, in this case the first condition is triggered.

Here’s another example from Elixir School’s Concurrency Section

defmodule Example do

def listen do

receive do

{:ok, "hello"} -> IO.puts "World"

end

listen

end

end

iex> pid = spawn(Example, :listen, [])

#PID<0.108.0>

iex> send pid, {:ok, "hello"}

World

{:ok, "hello"}

iex> send pid, :ok

:ok

In this example, spawn/3, takes a module name, a function in that module, and the initial state of the mailbox. We send a message to the process which then matches it, so “World” is returned. In the second send/2 no message is matched so nothing is returned from listen/0. You’ll notice that listen/0 is a recursive function. That’s because a process will die after the execution of the function, so we call listen/0 again to ensure that messages can continue to be handled.